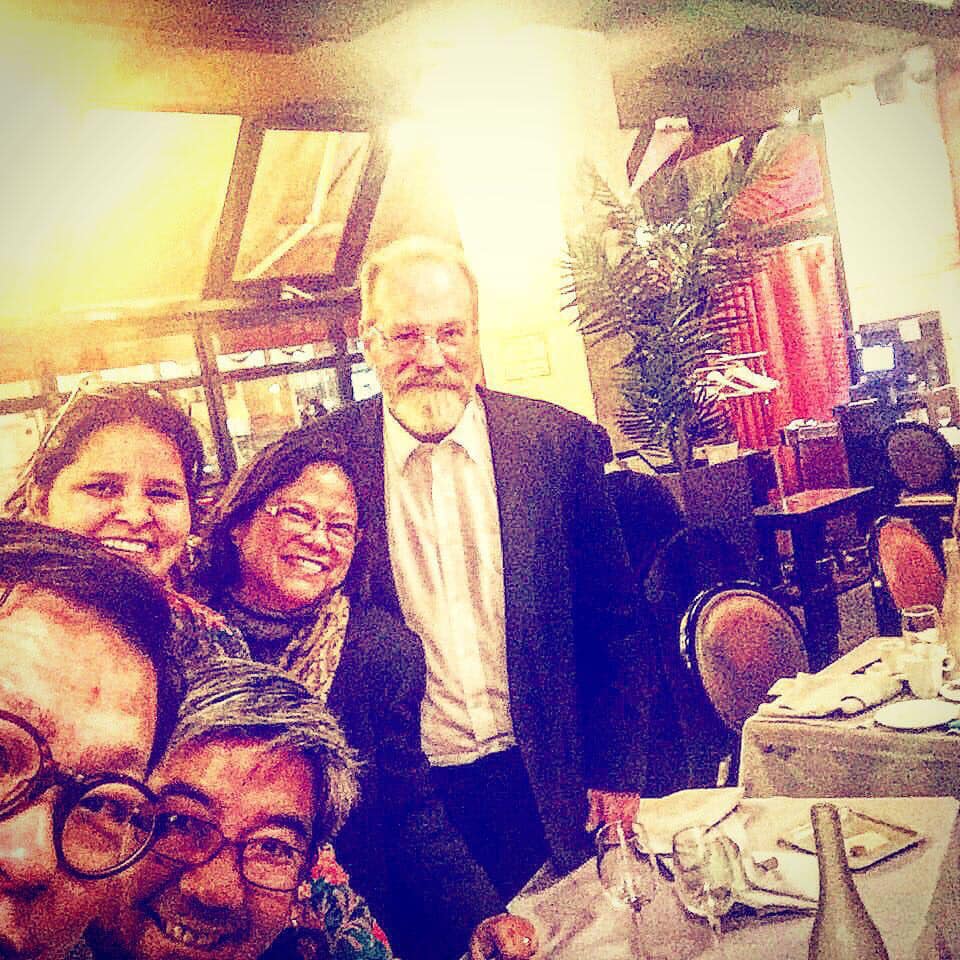

“There are salacious rumors going around saying our planet is burning and that you are no longer around. Only the latter is false. Along Rue de Dunkerque I passed by Terminus Nord the other day and paused, remembering when you walked in by chance, with lovely Shruti, and later Athena joined. Sze Ping and I were arguing loudly, as always, over langoustines, and you came over, wondering what the ruckus was about. Of course it was the usual nothing—who had the bigger oyster and who snored worse, and we wondered whether Sze Ping’s T-Rex arms could take a selfie that could capture all of us, which he did. You were in Gare du Nord, Steve Sawyer, and then again past Strasbourg as the train sped towards Frankfurt and turbines tall and spinning and gleaming, proclaimed that you would live forever. Because that is what you fought for, that so many others can live free with other species, with joy and family and friends, acts of kindness and love justifying our tiny blip in the universe.”

I posted this on Steve Sawyer’s Facebook tribute page in September 2019. Whenever the memory of Sawyer pops up, which can be often, I write a small note, my way of saying his name quietly. As my daughter Luna framed it for me years ago, when she saw wind turbines on the horizon while we were on a train in Europe headed to Steve’s memorial in Amsterdam, “Steve Sawyer sighting…”

Steve is almost Elvis-like now, because the energy transition revolution he pushed so hard to realize continues to roll out, but he’d also be the first to say it’s not fast enough, and that we need to fight harder using all the tools we have. His life of activism, especially in his last stint at the Global Wind Energy Council’s helm – to rapidly transform the private sector – personified Gandalf’s words: “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

I posted this on Facebook in October 2020:

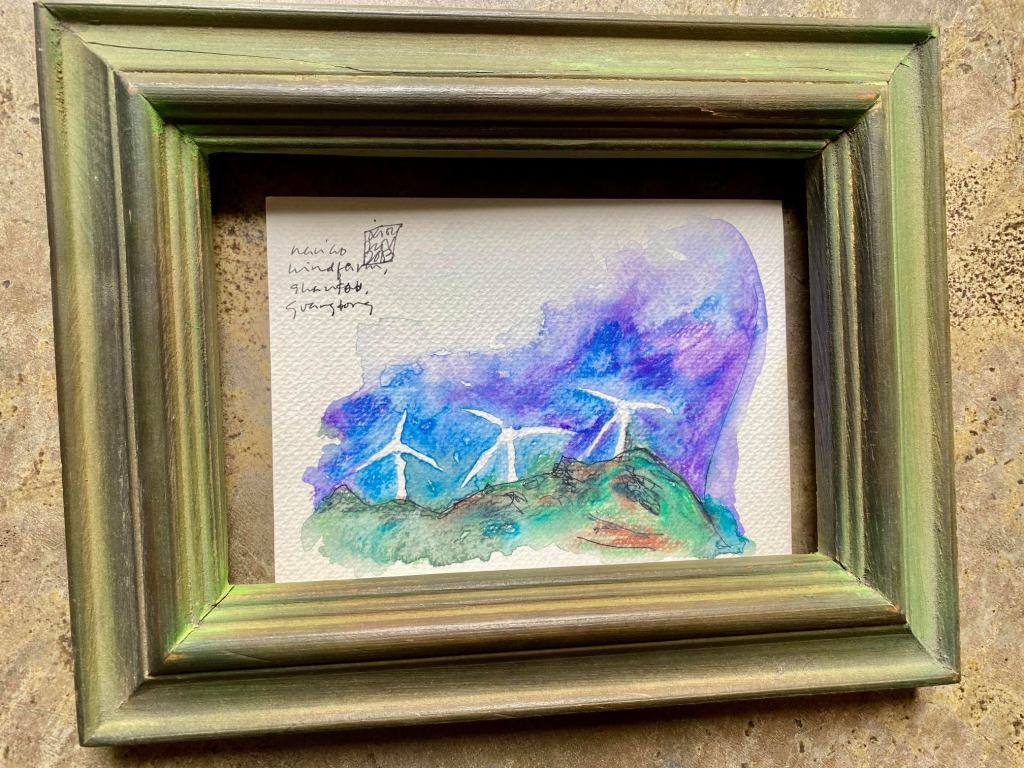

“Bizarro world GP story with a sketch: This is the Nan’ao windfarm in Shantou, Guangdong. Watercolor crayons, pen, and ink, November 2003. What was unforgettable? It wasn’t the wind turbines; a lot of people were laughing at us then when we propounded and eventually launched the report Wind Guangdong. (Look at how colossal wind is today in China, and it’s still flourishing). But that wasn’t the highlight. It was something else.

“I was with the Greenpeace International crew, with Sze Ping, Ateng Ballesteros, Steve Sawyer, Martin Baker, and Srini. Before 24 hours were done, Sawyer was beyond his grumpy self, and so was most of everyone, except SP and Sri. Sawyer and all, including myself, were in a manic, panicked, fearful sort of mode: imagine some of the most intense, ornery, unruly Greenpeace climate campaigners gathering in China and on their first morning they realize… There. Is. No. Coffee. Lots of tea with probably higher caffeine, but yes, no coffee.

“The big word was spoken silently with gnashed teeth-intensity: “Fuck.” I was briefly the savior that morning and my status lasted less than a minute. I had with me one satchet of Instant 3-in-1 coffee, which I promptly whipped out. I snipped a corner and sat on the floor to slowly empty the contents on a low glass table. A GP crew surrounded me, including Steve, and they stood menacingly quiet, backs hunched and peering closely at my hands. My head was bowed but my eyes were looking up so I certainly noticed them hovering over me, creepily silent and squinting. I divided the instant coffee powder into even lines like movie cocaine. Someone behind me was muttering “the lines are uneven” and another, I think Steve, mumbled “his portions are too fat.” And we found tiny tiny tea cups and dissolved the coffee and an unmitigated apocalypse was averted till the afternoon, when a runner finally found a far away cafe. And then it was time for gallons of beer and normal crazy shit.”

I first met Steve in 2001, when he headed the Greenpeace delegation to COP6bis, the UNFCCC emergency meet to save the climate talks after COP6 collapsed int the Hague. It was a privilege to have been part of teams led by such a stubborn, spectacularly sharp, curmudgeonly guitarist, a Tolkien nerd capable of discussing the intricacies of thermohaline circulation and meteorology as well as decadal changes in the cryosphere, while providing accurate figures whenever anyone asks him about daytime electricity price characteristics in Accra, Hanoi, Valencia, Riyadh, Santiago, Ankara, and Kingston, across power generation technologies.

Almost two weeks after his passing, on 12 August 2019, I had this published, in Steve’s tribute:

In Memoriam: Steve Sawyer

For a week I agonized over missing words.

I was invited to contribute to Letters to the Earth, a book due November and inspired by the global youth uprising and the Extinction Rebellion. The draft — a letter to my daughter — felt ready but for a paragraph that did not close well.

I managed to set aside messages that arrived early on 31 July, implying something terrible had happened to Steve. But the text from Bill Hare sharing Brian Fitzgerald’s obituary finally punched through the disbelief. Athena Ballesteros called an hour later, bawling. And so on the day of his passing the errant syllables finally rolled in and completed the sentence that had eluded me: “The gift of Bette Midler and Bonnie Raitt, Susan Sontag and Steve Sawyer.”

I sent the submission on its way and waited for confirmation of its receipt. And then I wept.

When I first encountered Sawyer, I already had twenty years of disobedience training.

I met him as he was presiding over a tense delegation meeting of Greenpeace at the basement of a godawful building in Bonn. The year was 2001 and we were a stone’s throw away from Hotel Maritim, a dreadful convention facility that was also the rescue site of the global climate negotiations. It was COP-6bis, so named because months earlier in the Hague, the sixth Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change had collapsed.

By the end of the Bonn talks, however, the climate agenda was back on track and I found myself smitten, not just with one but two crotchety men.

The question as to who was more cranky between them is occasionally posed by friends: was it scholarly Creedence Clearwater Steve or the eminent scientist Bill Hare? But Laetitia De Marez and I would always come to their defense and with vehemence assert that neither deserved the tag. It’s true, we’d say; one was denser than an over-kneaded bagel while the other was prone to corny jokes. It was also equally true that one was grouchy and the other unequivocally grumpy. But cranky? No way.

I remember the feeling they both inspired in me: I would have defeated King Kong and Godzilla just to prove I was worthy of their most difficult assignment.

In 2006, near the close of the climate talks in Nairobi, I remember the way Bill provided to a Greenpeace huddle a forensic analysis of the latest watered down negotiations text and how after, Steve calmly framed points of convergence and action. Sawyer spoke with such incredible clarity that the campaigners were still staring at him intensely in silence even though he had already closed the meeting.

“What are you looking at?” Steve had wondered aloud. “There’s little time. Run!” Which is what some of us did.

I found myself running alongside the brilliant Brazilian scientist, Dr. Carlos Rittl. After two minutes Carlos and I stopped mid-stride and asked each other at the same time: “Why are we running?” We had no clue and we walked back to Sawyer laughing, arms on each other’s shoulders, and we laughed so hard we couldn’t speak for a while.

Steve did not require bombast in order to lead. He led by example and no one worked harder than him.

I’ve always wondered how it was possible that every day for the two weeks of a climate talks slog I’d be up by 0600 to get breakfast and prepare for the day by going through updates and analysis of the previous night. Yet by the time I reached the dining area, I’d see Sawyer — all dressed up, his breakfast finished, campaign briefs already written and littering a table — barking out the day’s logistical needs on his mobile phone. Two or three hours past midnight when it was time for sleep, Steve would still be up typing away on his laptop or, earphones on, having an animated discussion.

We were The Tuskers in 2006, a Greenpeace team named after the Kenyan beer that had become our companion. Steve worked closely with Mhairy Dunlop and Natalia Truchi on communications, as he did on politics with John Coequyt and Kaisa Kosonen. And with George Watane he’d arrange the daily pick up and delivery of campaign collaterals and the Greenpeace team through the White Gazelle, a minibus built without shock absorbers that moved our innards about every trip. We bounced around so much there were days Gabriela von Goerne would find her bladder near her elbow while Steven Guilbeault would realize his kidney was resting beside his heart.

With unwavering resolve, Steve (and Bill) guided unruly individuals using only intellect, integrity, and the profound sense of humility that comes with knowing just how close the world was already back then to the climate precipice we find ourselves in today.

Steve could switch from Tolkien’s Lothlorien to Cream and Clapton to Shell’s murderous playbook, and if you asked him the difference down to Euro cents between the electricity rates of Bamako and Berlin, he’d tell you. He always looked to the future and working with him felt as if he treated each day as a decisive moment, whether to enjoy great blues or to confront the pivotal juncture where humans choose to act or remain indifferent.

“I sincerely hope,” said Sawyer on 05 October 1991, the day after the Antarctic Treaty was signed, “that future historians will identify this day as a turning point towards the development of a global awareness that we as a species, we must go about the business of life on this planet as if there was a tomorrow to be concerned about.” Today, “this day” means every day.

In his announcement, received with sorrow on 31 July by thousands of campaigners around the world and doubtless written with great difficulty because of their close ties, Bill wrote about his comrade and friend Steve and his “storied life, well lived… a true Rainbow Warrior, a leader of, and within, Greenpeace for decades before leading the Global Wind Energy Council [GWEC].” Bill noted the great respect accorded to Steve “by friend and foe alike for his acute intelligence, broad knowledge, strategic sense and tactical campaigning – and for his sense of humour.”

“On the frontline of the climate wars from 2000 onwards,” wrote Bill, “Steve was there confronting those opposed to action and encouraging campaigners everywhere to keep focused and effective.”

Steve always walked the talk. During his stint as general secretary of GWEC, wind power “became one of the world’s most important energy sources” with global wind installations growing from 74GW to 539GW, covering places “such as India, China, Brazil and South Africa.” He was a tireless thinker, writer and speaker.

Today Sawyer’s name is forever etched among Marshallese citizens who remember the Greenpeace expedition he had led in 1985 to evacuate from the islands of Rongelap over 300 residents, many distraught, deformed, and gravely ill. They were first and second generation victims of the 1954 nuclear test at the Bikini Atoll, which the US had detonated to ascertain the impact of a nuclear device several magnitudes stronger than the Hiroshima bomb and which had permanently blanketed neighboring islands with radioactive material. The damage inflicted on the people of the Marshalls was so severe a dome was eventually built in order to contain the radiation, a concrete structure rising seas today threaten to inundate.

Losing Steve feels staggering and I find myself grasping at words to say to Kelly Rigg, Steve’s life-long partner and comrade, and to their daughter Layla, who brings sunshine wherever she goes; and to their son Sam, whom I’ve never met. Maybe I can say once upon a time I helped Steve choose a set of Bionicles for him and I can tell Layla how thrilled I was to receive a box of beautiful Brouwerij ‘t Ij craft beers from her. And then what? I am not part of their family, yet I feel gutted and orphaned.

Perhaps it is enough for now to recount what Auden Schendler and Andrew P. Jones wrote in October 2018, because their words best describe to me the life Steve Sawyer lived. In my heart he was mythical yet real, and he was always true.

We “endow our lives with some of the oldest and most numinous aspirations of humankind: leading a good life; treating our neighbors well; imbuing our short existence with timeless ideas like grace, dignity, respect, tolerance and love. The climate struggle embodies the essence of what it means to be human, which is that we strive for the divine.”